By: Daniel Reynolds

It’s your childhood, circa 1993 or ‘94, and you are handed a book by your parents. It’s slim, only 60 odd pages, a child’s version of a story titled The Time Machine. It’s written by H.G. Wells, though he died in 1946 and this version was first published in 1986. You do not notice this at the time. There are a smattering of illustrations dispersed in this book’s pages. Some of these pictures, depicting cave-dwelling monsters groping after a man lost in the dark, terrify you. You do not forget this.

Later, it’s 2004 and you take a science fiction literature class in university. You want to read books, and write about them, and not worry about the rest of your course work. You are presented with the full edition of Wells’ The Time Machine. The tale now reads like a genteel odyssey, one man’s wanderings through time for no other reason than to see what’s there. The book’s monsters don’t scare you anymore — they seem almost quaint, like desperate little nocturnal apes — but something else does. Time continues to pass.

H.G. Wells says whaddup.

Consider the year 1895. H.G. Wells gets his serial novel The Time Machine published in The New Review. This is before science fiction, in all its various forms, was a thing, before it knew what it was to become. The book is only 85 pages long, yet travels across some 800 millennia. Wells is credited as the first author to popularize the notion of time travel. It’s not the last time the concept pops up in fiction, though he couldn’t have known that then.

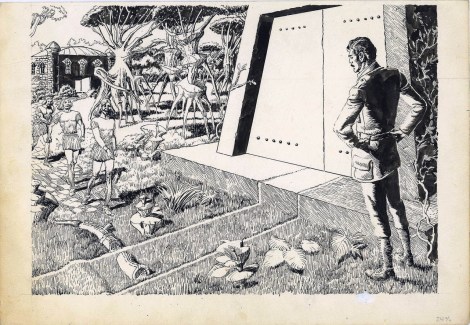

His protagonist, known only as the Time Traveller, is a man of science who invents the titular machine which allows him to visit the past or the future. He opts for the latter and, after jumping to the year 802,701, finds a verdant, evolved planet populated by two dominant species — the Eloi and the Morlocks. The former is a species of child-like hedonists, unconcerned with industry or ambition; the latter exists in subterranean caves, surrounded by the machinery of past ages. Neither species is particularly communicative. The suspense of the book begins once the Time Traveller, barely out of sight of where his house once stood, loses his machine, becoming stranded in time.

Wells’ writing is concerned with more than just visions of a future Earth however. He was born in 1866 in the United Kingdom, which locates him in a time after the Industrial Revolution. It was a period that saw the rapid invention, expansion and application of technology, allowing man to change the world at a rate heretofore unseen. But for every advance, there was always an owner and an operator, a class division that fuels the themes of Wells’ original work. It’s easy to project who among his contemporaries were to become the feckless Eloi, and who would be gradually driven underground to labour. That the Morlocks rely on the Eloi, the literal “upper” class, as their sole source of food is an irony that was surely not lost on Wells. The book’s action may be modest, but its thinking is not.

Time travel is for the gentlemanly class only.

But now it’s 1960 and the world is different again. Wells’ story is adapted into a film for the first time, with George Pal directing and Rod Taylor cast as the Time Traveller. Despite winning an Oscar for Best Special Effects, it’s not a particularly good film — the action is stilted and comically considered, and it’s suffused with an eye-rolling tone of paternalism. It does, however, capture some of the book’s spirit of armchair adventure. Like the source text, its framing device is kept simple: a drawing room of learned men listen to the whopping account of the Time Traveller and his fantastic journey.

Here though, rather than speed directly into the distant future as in the book, the Time Traveller makes some thematically convenient stops first. What he learns from visits to 1917, 1940, and 1966, is no matter the era, warfare follows man. It’s the last such stop that drives the film’s future. In lieu of Well’s class-driven evolution, mankind is instead divided by a Cold War-inspired nuclear attack; the surface survivors becoming the Eloi, and those escaped to fallout shelters becoming the Morlocks. In this way, the film stands totally apart from Wells’ original thinking, and yet respects his thematic intent. And as a prognostication, it felt grimly possible at the time.

It does not come to pass however, and by 2002 there is another film adaptation. This one is directed by Simon Wells, the great-grandson of H.G, and stars Guy Pearce. Unlike the previous film, with its turgid pacing, this is a modern movie of the post-blockbuster era — the action is kinetic to a fault and the special effects are considerable. (Coincidentally, it too was nominated for an Oscar, this time for Best Makeup.) The time machine here appears as a glittering chariot rather than the velvety sleigh of the previous iteration. And the subsequent jumps through time, which move to the near future of 2030 and then far beyond, evoke something approaching distant wonder. The simplicity of Wells’ original story, however, is given a radical and unnecessary makeover.

Guy “I’ve made some weird choices in my career” Pearce

In this telling, the Time Traveller is given a name and a purpose. He is Alexander Hartdegen, professor and inventor, and also, a man in love. By an unfortunate chance of fate, his bride-to-be is killed by a mugger on the very night he proposes to her. The invention of time travel becomes therefore not just an idle curiosity, but a mission; a grieving Hartdegen seeks to change the past. In a different era, one not inundated with stories of paradoxes, this would feel novel rather than just repetitive. Hartdegen looks to the future for a solution, but this hoary narrative idea tires the film out before it even gets there.

Hartdegen’s search for answers finds a world of possibility undone by its failure to consider the implications of its progress. In this case, man’s desire to transcend the planet proves disastrous. An explosive moon excavation has gone awry, celestial order is disturbed, and the Earth is thrown into disarray. It’s a cinematic idea somehow both ridiculous and appropriate, considering the age in which it was produced. After all, it was just a few years earlier, in 1998, when asteroids were hell-bent on destroying the planet.

Even considering these differences, both film adaptations of The Time Machine exist along the same thematic continuum of Wells’ original work. Where his tale reflected on the evolution of humanity through the lens of class and industry, the films each capture something of their time. In 1960, it’s an intense preoccupation with war. In 2002, underneath narrative clutter, there’s a nod towards man’s misplaced faith in technology. And yet despite this easy mirroring, these film adaptations do not address the story’s most arresting scene.

At the end of the 1960 film, after vanquishing the Morlocks, the Time Traveller journeys back into the future filled with hope. Armed with his knowledge and ingenuity, the Time Traveller plans to educate the Eloi and rebuild their world into the Eden he believes it should be. In 2002, the feeling is similar. Hartdegen casts aside his doomed attempts at changing the past and embraces the idea of heroic self-sacrifice. He detonates the time machine itself to kill off the Morlocks (don’t ask), trapping himself in the new peaceful future he’s helped create. To further ensure a happy ending, both heroes even find new female companions to keep them company. These films both end without acknowledging that time itself does not.

This future is not so bad, right guys? Guys???

As the Time Traveller of fiction plots to reclaim his machine and escape the future, he discovers a museum of relics from the recent and not-so-recent past. There is a large white sphinx, a green porcelain palace and pavilions housing the clueless Eloi. The time machine has been dragged into a chamber beyond a set of bronze doors. Everything is in a state of casual ruin; there is nothing left to save. At one point, trapped in a nighttime landscape filled with hungry Morlocks, the Time Traveller razes a forest to flee capture. He escapes, but his companion (yes, he too has a companion), a female Eloi named Weena, is left for dead. The story’s last vestiges of optimism go with her. The Time Traveller eventually reclaims his machine, sets the controls to a point in an even more distant era, and leaves this all behind.

There’s a stream of theology — known as Eschatology — concerned with the final events of history and the end of the world. Religions grapple with this in different ways, portraying the end times as a period of destruction, regeneration, unity and rebirth, complete with the requisite godheads and mythic figures. Scientific thought, even in 1895, is colder in its assessment; Wells’ writing fully embraces this darkness. His Time Traveller finds a world eroded to its basic components, with the barest signs of life — first giant moths and hulking crabs, then, even further along, just lichen and an indistinguishable mass flopping about in a shallow sea. The sun hangs huge and red in the sky. The idea of world reborn feels decidedly far away. Or impossible.

Back again in the 2002 film, this future is portrayed briefly as an odious alternate timeline, one that can only be avoided if the evil, well-spoken leader of the Morlocks (a bewigged, albino Jeremy Irons) is destroyed. The 1960 film avoids these horrifying visions entirely. The time travellers of the films revel in their romantic hope for the future. Wells bravely concludes his story in a truer way; his protagonist’s end is far more ambiguous. He disappears somewhere in time with no acknowledgement of his ultimate fate.

********

You are in 2016 now. You look out your window and try to imagine what the world will look like in 20, 50, 100 years. By then you and everyone you know will be dead. How much further can you see? Where does any of this end? It’s possible to envision a new film adaptation of The Time Machine predicting a world torn asunder by political unrest or ecological catastrophe, pressing issues of this current time. For such a slight and specific piece of fiction, Wells’ work certainly achieves a rare timelessness. But the images of that one chapter, a mere five pages, document an end that seems inescapable.

You read The Time Machine as a child, and again as an adult; you watch and rewatch the films, and learn of even more adaptations for TV and radio. Wells’ story has gone on to inspire other works in various media, and stands as one of the founding pillars of the science fiction genre. All of this is stored and saved for the foreseeable future. But this too is ironic and not a little scary to contemplate. For over all of it looms not just your erasure and the eventual annihilation of mankind, but a more direct question posed by the tale itself: Does any of this even matter?

You long for the simplicity of monsters in the dark.

Impressive

You forgot to mention that halfway through filming of the 2002 adaptation, Simon Wells came down with a severe case of “extreme exhaustion”, and had to be replaced by Gore Verbinski for the remainder of the shoot.